The controversial figure castigated Maratha ruler Shivaji for sending back the daughter-in-law of the Muslim governor of Kalyan, whom he defeated.

Decades before the sexual assault of women during the 2002 Gujarat and 2013 Muzaffarnagar riots, Hindutva propounder Veer Savarkar justified rape as a legitimate political tool. This he did by reconfiguring the idea of “Hindu virtue” in his book Six Glorious Epochs of Indian History, which he wrote in Marathi a few years before his death in 1966.

Six Glorious Epochs provides an account of Hindu resistance to invasions of India from the earliest times. It is based on historical records (many of them dubious), exaggerated accounts of foreign travellers, and the writings of colonial historians. Savarkar’s own febrile and frightening imagination reworks these diverse sources into a tome remarkable for its anger and hatred.

Savarkar’s account of Hindu resistance is also a history of virtues. He identified the virtues that proved detrimental to India and led to its conquest. He expounded his philosophy of morality in Chapter VIII,Perverted Conception of Virtues, in which he rejected the idea of absolute or unqualified virtue.

“In fact virtues and vices are only relative terms,” he said.

Virtues or vice?

Savarkar added that the test of determining what is virtue or vice is to examine whether it serves the interests of society, specifically Hindu society. This is because circumstances change, societies are always in a flux. What was deemed virtuous in the past could become a vice in the present if it is detrimental to mankind, he said.

For instance, said Savarkar, the caste system with its elaborate rules of purity and pollution helped stabilise Hindu society. But some of these rules became dysfunctional, degenerating into “seven fetters” of Hindu society.

These shackles, according to Savarkar, were untouchability, bans on drinking water from members of other castes, inter-caste dining, inter-caste marriage, sea-voyage, the ban on taking back into the Hindu fold those who were forcibly converted to Islam or Christianity, and ostracism of those who defied these prohibitions.

These “seven fetters” proved advantageous to the Muslim conquerors, wrote Savarkar, because they exploited caste rules to increase their population.

The conquerors forcibly converted Hindus who had been defeated, provided them with food and water, abducted women who were either kept as concubines or wives, certain that the ban on taking them back into the Hindu fold left them with no option but to live as Muslim, the Hindutva propounder wrote. This meant the “transformation of a man into a demon, the metamorphosis of a God into a Satan”.

Rape as a political tool

It is in this paradigm of ethics that Savarkar mooted the idea of rape as a political tool. He articulated it as a wish, through a question: What if Hindu kings, who occasionally defeated their Muslim counterparts, had also raped their women?

He expressed this wish after declaring, “It was a religious duty of every Muslim to kidnap and force into their religion, non-Muslim women.” He added that this fanaticism was not “Muslim madness”, for it had a distinct design – to increase the “Muslim population with special regard to unavoidable laws of nature.” It is the same law, which the animal world instinctively obeys.

Sarvarkar wrote:

“If in the cattle-herds the number of oxen grows in excess of the cows, the herds do not grow numerically in a rapid number. But on the other hand, the number of animals in the herds, with the excess of cows over the oxen, grows in mathematical progression.”

He cites examples from the human world too. For instance, he wrote, the African “wild tribes” kill only their male enemies, but not their women, who are distributed among the victors. This is because these tribes consider it their duty to increase their numbers through the progeny of abducted women. Similarly, he wrote that a Naga tribe in India kills women of rival tribes whom they can’t capture because they believe, rightly so, that paucity of women would enhance the possibility of their enemies dwindling in number.

Savarkar said that the Muslim conquerors of Africa too followed this tradition. Immediately thereafter, he spoke of the well-wishers of Ravana who advised him to return to Rama his wife, Sita, whom he had abducted. They said it was highly irreligious to have kidnapped Sita. Savarkar quotes Ravana saying, “What? To abduct and rape the womenfolk of the enemy, do you call it irreligious? It is Parodharmah, the greatest duty!”

It is with the “shameless religious fanaticism” of Ravana that the Muslims, from the Sultan to the soldier, abducted Hindu women, even the married ladies of Hindu royal families and notables, wrote Savarkar, adding that this was to increase the population of Muslims, to demographically conquer India, so to speak.

Savarkar is venomously critical of Muslim women who, “whether Begum or beggar”, never protested against the “atrocities committed by their male compatriots; on the contrary they encouraged them to do so and honoured them for it”.

Savarkar, even by his own standards, takes a huge leap by claiming that Muslim women living even in Hindu kingdoms enticed Hindu girls, “locked them up in their own houses, and conveyed them to Muslims centres in Masjids and Mosques”.

Muslim women were emboldened to perpetrate such atrocities because they did not fear retribution from Hindu men who, argued Savarkar, “had a perverted idea of women-chivalry”. Even when they vanquished their Muslim rivals, they punished the men among them, not their women, he said.

“Only Muslim men alone, if at all, suffered the consequential indignities but the Muslim women – never!” wrote Savarkar.

When Shivaji was wrong

This regret prompts him not to spare those who commend Shivaji for sending back the daughter-in-law of the Muslim governor of Kalyan, whom he defeated, as well as Peshwa Chimaji Appa (1707-1740), who did the same with the Portuguese wife of the governor of Bassein.

Savarkar wrote:

“But is it not strange that, when they did so, neither Shivaji Maharaj nor Chimaji Appa should ever remember, the atrocities and the rapes and the molestation, perpetrated by Mahmud of Ghazni, Muhammad Ghori, Allauddin Khalji and others, on thousands of Hindu ladies and girls…”

Savarkar’s febrile imagination now flies on the wings of rhetoric. He writes:

“The souls of those millions of aggrieved women might have perhaps said ‘Do not forget, O Your Majesty Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj and O! Your Excellency Chimaji Appa, the unutterable atrocities and oppression and outrage committed on us by the sultans and Muslim noblemen and thousands of others, big and small.“Let these sultans and their peers take a pledge that in the event of a Hindu victory our molestation and detestable lot shall be avenged on the Muslim women. Once they are haunted with this dreadful apprehension that the Muslim women too, stand in the same predicament in case the Hindus win, the future Muslim conquerors will never dare to think of such molestation of Hindu women [emphasis added].”

Their chivalry was perverted, said Savarkar, because it proved highly detrimental to Hindu society. This chivalry was “suicidal” because it “saved the Muslim women (simply because they were women) from the heavy punishment of committing indescribable serious crimes against Hindu women”, Savarkar laments.

Even worse, he said, was the foolish notion among the Hindus that to have “any sort of relations with a Muslim woman meant their own conversion to Islam”. This belief became an impediment to Hindu men inflicting punishment on the “Muslim feminine class [fair (?) sex]” for their atrocities [words in parenthesis Savarkar’s].

Savarkar’s readers cannot but see that he has overturned the code of ethics and freed the Hindus from the shackles that prevent them from descending into barbarism. But Savarkar doesn’t seem convinced of his persuasive powers.

So under a subsection titled, But If, he seeks to hammer in his point. He asks readers:

“Suppose if from the earliest Muslim invasions of India, the Hindus also, whenever they were victors on the battlefields, had decided to pay the Muslim fair sex in the same coin or punished them in some other ways, i.e., by conversion even with force, and then absorbed them in their fold, then? Then with this horrible apprehension at their heart they would have desisted from their evil designs against any Hindu lady.”

He adds:

“If they had taken such a fright in the first two or three centuries, millions and millions of luckless Hindu ladies would have been saved all their indignities, loss of their own religion, rapes, ravages and other unimaginable persecutions.”

Thus, the use of rape as a political tool stands justified.

But why should Savarkar’s idea of rape as a political tool apply today, given that Six Glorious Epochs deal with India’s past?

This is because Savarkar very explicitly stated that a change of religion implies a change of nationality. It was Savarkar, not Muhammad Ali Jinnah, who first categorised Hindus and Muslims as two nations. From the Hindutva perspective, the two nations – Hindu and Muslim – have been locked in a continuous conflict for supremacy since the 11th century.

In the Savarkarite worldview, only those ethical codes should be adhered to which enable the Hindus to establish their supremacy over the Muslims. Thus, he reasoned, it is justified to rape Muslim women in riots because it is revenge for the barbarity of Muslims in the medieval times, whether proven or otherwise. After all, today’s riots are a manifestation of the historical conflict.

This is why BJP leaders clamour to celebrate the heroes of what they call Hindu resistance. The most recent example of this trend is Union Minister VK Singh, who wants Delhi’s Akbar Road to be renamed after Maharana Pratap. It is from Savarkar they have got their cue.

Later in Six Glorious Epochs, Savarkar adopted a distinct Nietzschean tone to cry out: “O thou Hindu society! Of all the sins and weaknesses, which have brought about thy fall, the greatest and most potent are thy virtues themselves.”

These virtues were cast aside in Gujarat in 2002 and Muzaffarnagar in 2013. That is something to remember as some people come out to pay homage to Savarkar who was born on this day 133 years ago.

This is the second article in a two-part series on VD Savarkar. The first part can her read here.

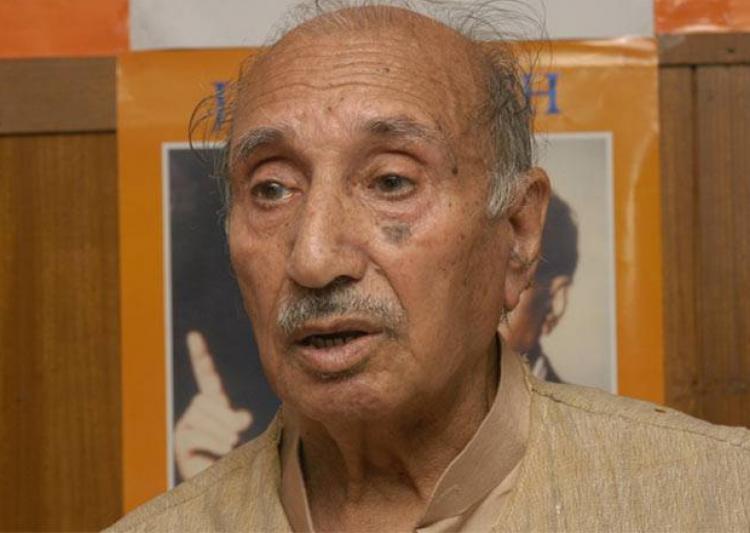

Ajaz Ashraf is a journalist in Delhi. His novel, The Hour Before Dawn, has as its backdrop the demolition of the Babri Masjid. It is available in bookstores.